Poems on Obsolescence by the “Elders” at LIFE

For the past six years I’ve taught a weekly poetry class at a senior day center called LIFE (Living Independently for Elders). This week, I learned that one of my oldest students, who had moved into a nursing home about a year ago, had passed away at the age of 94. Helen Brown had a sharp memory, a lyrical way with words, and impeccably legible handwriting (another “technology” about to disappear). She was also fearless in recounting some of her tougher life experiences, including a “whooping” at the hands of an aunt one summer, and her first encounter with racism in a rest stop outside of Boston when she was seven that made her realize she would find bigotry even “as far north as she could travel.”

I often assign my students to write about jobs they held or technologies and other everyday experiences that were once commonplace and now obsolete. As I collected these poems, I realized that with the passing of Helen Brown, every one of these students whose poems I feature here has died. All the more reason for Obsolescing to celebrate their long lives and vivid reminiscences this Poetry Month.

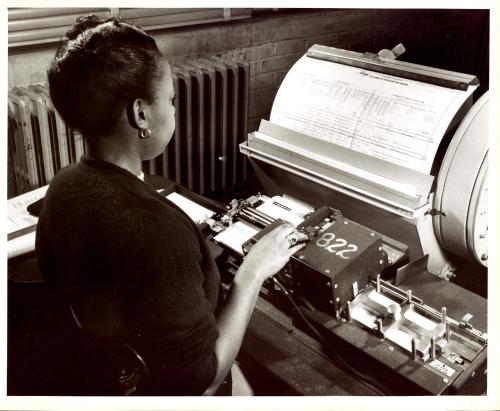

Keypunch Operator entering data for 1950 census

Keypuncher

by Helen Brown

You transcribe data.

You get messages on the wireless, which is verified.

You punch them into little cards.

That’s more or less

the start of the computer.

I didn’t know that at the time.

When I retired they

were just beginning

to store information

on disks.

The cards were

the first storage,

more or less.

We had shift work.

35 people at a time.

We didn’t take our breaks

at the same time.

We were keeping up

with deliveries.

We were allowed to

drink coffee at our desks.

The whole 35 couldn’t

take a break

at the same time.

Whatever had to be corrected

or tracked down couldn’t be

interrupted.

We had different

lunch hours.

35 people

broken down

in sections.

Phones

Phones

by Zettie Brown

Phones that we had

Long ago

The phone numbers

Had letters for you

To call

Now we use numbers

To dial

Someone

All the time

Our phone was

Round

In the middle

Control

by Zettie Brown

I miss the old TV that used

To be in the family room,

That you just turned the knob

And it came on. Now

You have remote control

That you push, and sometimes the

Show is not what you want

To see.

Start all over again.

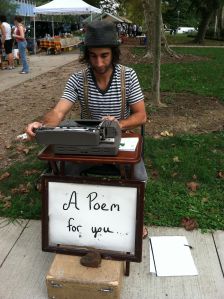

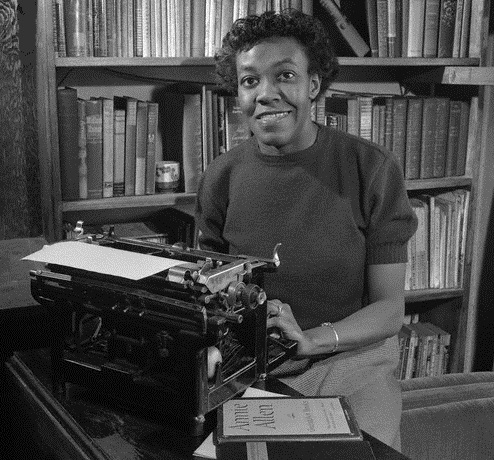

Poet Gwendolyn Brooks and her Royal Corona 6

The Typewriter

by Delores Lee

In order to correspond with my neighbors and others

I would have to sit at a table

And start typing on my typewriter.

You had a choice of pica or elite.

Pica was the small type.

I preferred elite

Which was the large letters.

The correspondence looked more

Official in the large type.

Nowadays the accepted way to correspond with others

Is to use e-mail.

There is a lack of warmness,

Or the friendliness

That you felt with a typed letter.

E-mail seems abrupt and cold to me,

Rushing through time.

The

typewriter

moved

slowly.

I miss the ability to erase an error.

There was a key that said “Correction.”

You could make the correction right away.

What I Miss About the Icebox

by Beverly Braxton

Emptying the pan.

The pan was always cool even though it was

On the floor, it had no smell.

It made a blob sound when the

Ice melted into the pan. The ice

Box had an opening for you to

Slide out the ice pan where the water

Would always splash on

You.